I.

I am particular about pantyhose. I can’t stand pilly pantyhose or hose with those lines and pulls throughout them. In my eyes as a child, there existed only one brand of pantyhose—L’eggs. My Grandmother wore only L’eggs and she wore them always. Each day she wore fuchsia lipstick and fuchsia nail polish, a skirt and matching blouse, and pantyhose underneath. The pantyhose were always “nude.” I thought nude hose were the most ladylike and elegant thing in the world because, in my eyes, my grandmother was a perfect Texas lady.

I traveled some with my grandmother, and every morning we would wake and order room service. She would stay in her housecoat and slippers until the room service arrived. She often packed for me a pair of pink satin slippers and matching quilted robe that buttoned up the front. This is what a lady wore in the morning. Once the food arrived, she would start in on her pot of coffee and basket of pastries and begin to get ready for the day. She would bathe and, afterwards, walk around the hotel room in her shower cap without any clothes on. I looked shyly away, stealing curious glances at her full-figured form. Then she would put on her pantyhose. Perched on the edge of the bed, she would skillfully—deftly really—usher the material from her toes up to her hips, somehow squeezing each beautifully meaty thigh into its tight nylon casing.

My grandmother often packed several pairs of pantyhose, but occasionally we had to go to the drugstore to buy her a new pair. And with each trip to the pantyhose aisle, my world expanded just a little. Maybe you remember the L’eggs packaging of the early eighties? Each pair of hose was wound tightly into a small ball and packed securely into a sleek, indestructible, tidy plastic egg. The egg was smart. It was modern. And the expansive display of plastic eggs—each one protecting a fine, delicate, intimate pair of nylons—offered you whatever your heart desired: powder, peach, golden dusk, sun beige, tan, jet black, sheer, opaque, matte, or shimmer. L’eggs gave you freedom of choice; L’eggs were American.

I liked the sleek modern feel of the plastic egg. I loved that something that covered two legs from top to bottom could be balled up to the size of my fist. I knew the advertisement surely must be true:

Our L’eggs fit your legs, they hug you, they hold you, they never let you go.

I waited eagerly for the day when I would graduate from white cotton tights to L’eggs pantyhose.

And in the meantime, I treasured the eggs. Because my grandmother had a beautiful travel case made just for pantyhose, I was allowed to keep each plastic egg she’d purchased, now emptied of its valuable pith. And each plastic egg was a world of possibility—one could become a biodome for the observation of earthworms or tadpoles, another half-egg was the skirt to a belle’s ball gown. I even had a book entitled The L’eggs Idea Book: Dozens of Creative Projects. And with the help of this book, my plastic egg could be turned into any number of useful things: a sachet, desk accessory, stamp dispenser, sponge cup, magazine rack and storage organizer, picture frame, string and tape dispenser, tobacco canister, fisherman’s bait bucket, cactus planter, flower vase, vertical herb garden, place card holder, party favor, napkin holder, nut dish, vegetable centerpiece, candy and flower basket, sewing kit for travel, felt feathered friend, Indian tom tom, papier-mâché animal, bumble bee bank, a little white mouse, a puppet, Christmas ornament, Easter egg with a peek-a-boo window, candle holder, or a paperweight.

And then, just about the time I was finally old enough to wear nude stockings, something came into my life and turned my comfortable, naïve world of pantyhose on its head: it was Oprah.

One day Oprah had a guest on her show who told the audience that there was latent racism inherent in our everyday lives as Americans. She showed a big colorful map and said that in most atlases, Africa was disproportionately, inaccurately small compared to the United States. Africa was in fact three times larger in landmass and population; the map she held portrayed the landmasses with their appropriate sizes. And then Oprah’s guest started in on “nude” pantyhose. The term “nude,” she said, was racist because the pale, peachy color of “nude” hose is not the color of every person’s nude skin, but only the color of a white person’s nude skin.

After much thought, I decided that the woman was right—L’eggs pantyhose were racist! I told my grandmother what Oprah and her guest had said. To my surprise, my grandmother’s world wasn’t turned upside down by this revelation and she continued to buy the hose. I, though, determined never to wear L’eggs hose ever in my life as long as “nude” existed.

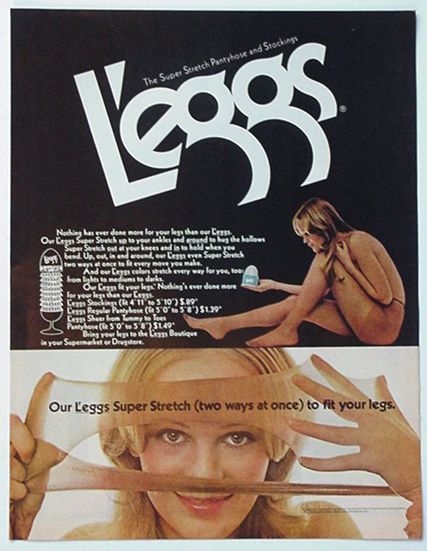

But deep down, I desperately wanted to. And the advertisements didn’t help. I learned that some women played basketball in their L’eggs:

And sometimes wearing pantyhose meant living dangerously:

II.

Equally potent on my young impressionable mind as the glamorous, freedom-bestowing side of pantyhose was the darker side of nylons. Pantyhose weren’t only used to create a barrier between a woman’s skin—or her propriety, really—and the world. They were also used to disfigure the face for disguise when committing a crime and to tie a person up, both against or according to his or her will. The pantyhose could even be used as a homemade noose in desperate times. This last use shows the mind-boggling contradiction of pantyhose—they are delicate enough to snag on a hangnail, but strong enough to hold the body’s weight. Delicate and strong: just like the modern woman.

In this contradiction, pantyhose became a literal and symbolic embodiment of the American propensity to cover up the unseemly. As a totem of a particularly American fear—the fear of the serial killer, armed robber, suicidal housewife, S & M practitioner living amongst us, or even worse, in us—pantyhose represent a fascination nestled deep in our national psyche: the idea that the average citizen, your neighbor, could harbor a dark or maybe even deadly secret, the idea that something so genteel could be so depraved, the idea that what you see may be a kind of artificial representation—the grotesque spots obscured—of what’s underneath.

The people who embody this, the crossing from apparently normal, even likeable, to deviant, easily become part of the cultural fabric of America over time. I would be lying if I said that no part of my initial desire to read Sylvia Plath’s work stemmed from an intrigue about her life—pretty, well-educated girl from the suburbs haunted by the death of her father and finally successful in her efforts to kill herself. And the list of outlaws who’ve captivated American fascination for decades because of their depiction as having been, at one point, “just like everybody else” or even “real nice and friendly” is endless—Bonnie and Clyde, Patty Hearst, Billy the Kid, Pretty Boy Floyd.

A more recent example is Colton Harris Moore, the teenage bandit who was captured after evading police detection for two years while committing burglaries—some small and some brazen (according to the Associated Press, he allegedly stole a plane in Indiana and, without any formal training, flew the plane over 1,000 miles to the islands off Florida’s coast). His popularity grew and grew as he taunted police with photos of himself and notes left at crime scenes. T-shirts were made with his picture and the words “Fly, Colton, Fly”; Facebook pages in his honor collected millions of fans; Youtube montages highlighted his achievements. Even his mother was cheering him on. When asked by a Time Magazine reporter about the crimes attributed to Colton, she said, “I hope to hell he stole those planes. I’d be so proud. But next time, I want him to wear a parachute.”

The boy is the product of a rough life—abuse, poverty—and seems to have been in the game (this is what it was to him) for the thrill of it. In fact, locals in his hometown speculated he cared little about the money and, instead, just wanted to experience the life he never had—he sometimes broke into a house just to take a bubble bath or steal ice cream from the freezer. In the Bahamas, Moore allegedly broke into a bar just to watch TV. A month before his ultimate capture, Moore left a handwritten note and $100 at a veterinary clinic in Raymond, Washington:

Drove by, had some extra cash. Please use this cash for the care of animals.

Colton Harris-Moore, (AKA: “The Barefoot Bandit”)

Camano Island, WA.

And it was this idea that made him so endearing to so many—maybe he was just a normal kid, good-natured at heart, who had somehow crossed a line. It is the friendly, good-looking, socially engaged person who goes bad who captures our imagination.

It is an appropriate coincidence that Colton Harris Moore goes by the nickname “Colt,” a word that conjures images of the Wild West, an indomitable animal in an indomitable terrain. The Colt revolver, like nylons, is as American as pie; both were freedom bestowing and empowering. Nylons allowed a woman the freedom to live her life without the restrictions of a garter belt. Now, with nylons, she could dance the jitterbug without fear of her hose falling down. She could wear shorter skirts without showing her garter belt or any skin.

The Colt revolver was a gun that fit discreetly at the waist. Even a woman could carry a handgun inside her clutch. In fact, one trope of the quintessentially American hard-boiled detective story is the sultry and glamorous woman who walks into the private eye’s office after hours and, after a shocking confrontation in which she confesses her involvement in the crime being investigated, the cool and composed dame pulls a revolver from her purse. Of course, the woman is always dressed in a fitted and very classic suit, her hair is perfectly coifed, and her legs are long and sleek in a pair of nude pantyhose.

III.

I was finally freed from my inner conflict between Oprah and L’eggs nude hose when the egg packaging was replaced. With the theme from 2001: A Space Odyssey playing in the background, the company announced the news: the days of the L’egg egg were gone. For twenty years the egg had been the L’eggs trademark, but now, in the early nineties, with the turn of the millennium approaching, it was time to think about the future. The new packaging required 38% less material, was printed on recycled paperboard, and was itself recyclable.

With the plastic egg retired, I no longer felt torn—I could live without L’eggs and the new cardboard packaging that looked more like a milk carton than a futuristic nugget of wonder.

And since then, my relationship with pantyhose has been defined by the search for the perfect pair of nylons. Recently I found it. At American Apparel. The only problem with the perfect pair of hose made by American Apparel is that it is made by American Apparel. American Apparel bills itself as a socially responsible company. American Apparel believes in justice for all, and what could be more American that that? Seven sexual-harassment law suits have challenged this progressive reputation over the last several years, with the founder Dov Charney at the center of the accusations. While none of these cases has led to a guilty verdict, American Apparel’s board removed Charney from his office as CEO last year.

The other inescapable problem of the company is that the quality of American Apparel products really is crap. Over the years I have bought a number of different items and amongst all these various American Apparel products, the common thread is unraveling thread. After just a couple of wears my clothes are coming apart at the seam. In the first month after discovering the perfect pair of nylons—American Apparel’s Sheer Luxe Pantyhose—I went through five pairs. The first pair ran as soon as I got them home and attempted to put them on for a Christmas party. I had to stop by the American Apparel store for a second pair on my way to the party. In a strange way, the fragility of the hose endeared me to the product even more. After all, it’s the gossamer quality of pantyhose that makes them so appealing in the first place. Deep down, I liked the idea of nylons so delicate that only a person with particular skill developed over years of dedicated practice could gently and confidently coax the material up the thigh without a single snag. I remembered the ease with which my grandmother did this, the way she unrolled the material at just the right speed as she shuffled her hands up her legs.

So until I find another pair of hose with such as smooth, buttery feel and even, tight knit, I will keep buying Sheer Luxe Pantyhose. Herein lies a problem: American Apparel is not cheap. Each pair of stockings costs twenty-four dollars and new resources from the earth. I cannot, in good conscience, throw away my runned pantyhose. Besides, as American culture moves away from pantyhose in celebration of exposed bare skin, my used pantyhose become relics worth preserving, a little piece of Americana, a slice of life from a past and irretrievable time and place. I sometimes wonder if others feel this way, or maybe it’s a nostalgia that runs just in my family.

Recently, at home for the holidays, I was faced with an unexpected drop in temperature, something colder than what I was used to in south Texas, something I hadn’t planned for in my packing. I only had jeans. My mom suggested I put on a pair of hose under my denim, and when I expressed hesitation—I didn’t want to run a good pair—she pulled out of her drawer a nest of old hose, all different shades of beige and tan, her skin color in summer and winter, even a smoke-hued pair, a relic from a past decade I’m sure. It was a collection of has-beens. I imagined each pair had lost its shape—gaped at the knees, bagged in the seat–maybe lost its sheen, but none had snagged yet. She was saving these. For what, I have no idea. Except, in that moment, that tangle of nylon seemed so full of possibility. The simplicity of their design and construction meant they were, essentially, raw material. With a snip or two, these pantyhose could be so much: sieve for juicing a lemon, tourniquet in an emergency, potpourri pockets for gifts, exercise band, blindfold. Or this, a layer of extra warmth.

IV.

My grandmother was moved recently from the six bedroom house she designed and had built in 1950, the home in which she raised her four children. She’d been living there by herself for the last four decades. When she was moved from her hometown of Amarillo, where she was raised as the youngest of thirteen siblings, to an assisted living home in Dallas, she was eighty-eight.

The last few times I visited her in Amarillo, she had already begun to slide down hill. She rarely left the house anymore because to leave the house meant hair done first at the beauty shop, full face made-up, nails painted red, brooch, earrings, and rings on, fuchsia lipstick on. It meant a pink silk scarf. It meant a pantsuit and pumps.

At some point she’d stopped wearing pantyhose. It had been years since she’d put them on herself, but even still, for someone else to help her guide them up her legs became too difficult, too off balance, too risky of a fall. I had never seen my grandmother in pants—not once a single pair of slacks or jeans—until the pantyhose became too much and my aunts began asking my grandmother’s helper to dress her in designer pantsuits they ordered for her from Neiman’s in Dallas.

What are pantyhose anyway, a layer of fake skin? A way to hide the blemishes, dimples, pocks, and scars. A way to keep everything together, under control and tight, a kind of violence we commit on ourselves.

The last time I saw my grandmother was the first time I visited her at her new home. When I signed in at the front desk, the desk attendant told me my grandmother was in the second floor lobby enjoying the music. At the top of the stairs, I saw a sitting room full of elderly residents positioned in chairs to face a man singing Sinatra and playing the piano. I found my grandmother in a wheelchair in the back row. I’m never sure these days if my grandmother knows me or is just really good at pretending she knows everyone. “Come on and sit with me, baby,” she said, and patted her thigh, as if it made sense still for me to sit on her lap, to sit with her in her wheelchair. But she didn’t pay attention to me for long. Quickly her focus shifted back to singing along, to waving her arms up high. She clapped to the beat, tapped her shoe on the metal footrest of her chair.

As I watched my grandmother in her wheelchair next to me, I was struck by her ability to keep the beat, to tap in time, to sing in tune. I had never seen her do any of this before. She had always been so poised, so measured and composed. But this day she moved her body and hands with a carelessness that bespoke freedom. When an elderly man came over to speak to his wife seated next to us, my grandmother introduced herself to him and said, “Come on and sit with me.” She patted her thigh but didn’t wait for an answer. She went back to the music, to closing her eyes, to singing along even if she didn’t know the words. A few minutes later, she introduced herself again to the man. Later I learned he lived on her hall.

Even now, my grandmother looked lovely. Her hair and nails were done and she wore a beautiful St. John pantsuit. Surely her caregiver had reminded my grandmother to put on her lipstick before she’d wheeled her downstairs for the music. That’s one thing she can still do on her own, like breathing—make her lips taut and drag the fuchsia point to all corners of her lips, rub them together, blot. One time when I was in Amarillo a few years earlier, I was loading up my grandmother to take her to the family Christmas party. My grandmother, one of only two remaining siblings of the thirteen, was the family matriarch and to her the family Christmas party was an important and never-missed event. My dad, who was sick and couldn’t go himself, called me just as I was about to help my grandmother out of her TV chair and into the car. “Remind her to put on her lipstick before y’all leave,” he said. It might have seemed odd, maybe even horrible, for him to tell me this, to care whether an eighty-five-year-old woman had her lipstick on, if I hadn’t seen it for what it was—a son’s best effort to maintain his mother’s chosen way of life, to keep up the things that were important to her even when she couldn’t.

When I called my dad later that night to tell him about my visit, I said she seemed happy in her new home. “She was dancing,” I said. “She was singing along and dancing. I’ve never seen her do that before.”

Quickly, without a thought, a knee-jerk reaction to protect his mom, my dad said, “She wasn’t the only one dancing was she?”

I didn’t have the heart to tell him she was. It was a kind of loss, we both knew, this freedom.