I.

I am particular about pantyhose. I can’t stand pilly pantyhose or hose with those lines and pulls throughout them. In my eyes as a child, there existed only one brand of pantyhose—L’eggs. My grandmother wore only L’eggs and she wore them always. Each day she wore fuchsia lipstick and fuchsia nail polish, a skirt and matching blouse, and pantyhose underneath. The pantyhose were always “nude.” I thought nude hose were the most ladylike and elegant thing in the world because, in my eyes, my grandmother was a perfect Texas lady.

I traveled some with my grandmother, and every morning we would wake and order room service. She would stay in her housecoat and slippers until the room service arrived. She often packed for me a pair of pink satin slippers and matching quilted robe that buttoned up the front. This is what a lady wore in the morning. Once the food arrived, she would start in on her pot of coffee and basket of pastries and begin to get ready for the day. She would bathe and, afterwards, walk around the hotel room in her shower cap without any clothes on. I looked shyly away, stealing curious glances at her full-figured form. Then she would put on her pantyhose. Perched on the edge of the bed, she would skillfully—deftly really—usher the material from her toes up to her hips, somehow squeezing each beautifully meaty thigh into its tight nylon casing.

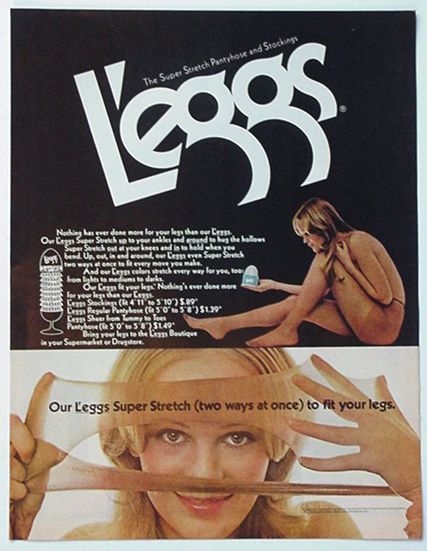

My grandmother often packed several pairs of pantyhose, but occasionally we had to go to the drugstore to buy her a new pair. And with each trip to the pantyhose aisle, my world expanded just a little. Maybe you remember the L’eggs packaging of the early eighties? Each pair of hose was wound tightly into a small ball and packed securely into a sleek, indestructible, tidy plastic egg. The egg was smart. It was modern. And the expansive display of plastic eggs—each one protecting a fine, delicate, intimate pair of nylons—offered you whatever your heart desired: powder, peach, golden dusk, sun beige, tan, jet black, sheer, opaque, matte, or shimmer. L’eggs gave you freedom of choice; L’eggs were American.

I liked the sleek modern feel of the plastic egg. I loved that something that covered two legs from top to bottom could be balled up to the size of my fist. I knew the advertisement surely must be true:

Our L’eggs fit your legs, they hug you, they hold you, they never let you go.

I waited eagerly for the day when I would graduate from white cotton tights to L’eggs pantyhose.

And in the meantime, I treasured the eggs. Because my grandmother had a beautiful travel case made just for pantyhose, I was allowed to keep each plastic egg she’d purchased, now emptied of its valuable pith. And each plastic egg was a world of possibility—one could become a biodome for the observation of earthworms or tadpoles, another half-egg was the skirt to a belle’s ball gown. I even had a book entitled The L’eggs Idea Book: Dozens of Creative Projects. And with the help of this book, my plastic egg could be turned into any number of useful things: a sachet, desk accessory, stamp dispenser, sponge cup, magazine rack and storage organizer, picture frame, string and tape dispenser, tobacco canister, fisherman’s bait bucket, cactus planter, flower vase, vertical herb garden, place card holder, party favor, napkin holder, nut dish, vegetable centerpiece, candy and flower basket, sewing kit for travel, felt feathered friend, Indian tom tom, papier-mâché animal, bumble bee bank, a little white mouse, a puppet, Christmas ornament, Easter egg with a peek-a-boo window, candle holder, or a paperweight.

And then, just about the time I was finally old enough to wear nude stockings, something came into my life and turned my comfortable, naïve world of pantyhose on its head: it was Oprah.

One day Oprah had a guest on her show who told the audience that there was latent racism inherent in our everyday lives as Americans. She showed a big colorful map and said that in most atlases, Africa was disproportionately, inaccurately small compared to the United States. Africa was in fact three times larger in landmass and population; the map she held portrayed the landmasses with their appropriate sizes. And then Oprah’s guest started in on “nude” pantyhose. The term “nude,” she said, was racist because the pale, peachy color of “nude” hose is not the color of every person’s nude skin, but only the color of a white person’s nude skin.

After much thought, I decided that the woman was right—L’eggs pantyhose were racist! I told my grandmother what Oprah and her guest had said. To my surprise, my grandmother’s world wasn’t turned upside down by this revelation and she continued to buy the hose. I, though, determined never to wear L’eggs hose ever in my life as long as “nude” existed.

But deep down, I desperately wanted to. And the advertisements didn’t help. I learned that some women played basketball in their L’eggs:

And sometimes wearing pantyhose meant living dangerously:

II.

Equally potent on my young impressionable mind as the glamorous, freedom-bestowing side of pantyhose was the darker side of nylons. Pantyhose weren’t only used to create a barrier between a woman’s skin—or her propriety, really—and the world. They were also used to disfigure the face for disguise when committing a crime and to tie a person up, both against or according to his or her will. The pantyhose could even be used as a homemade noose in desperate times. This last use shows the mind-boggling contradiction of pantyhose—they are delicate enough to snag on a hangnail, but strong enough to hold the body’s weight. Delicate and strong: just like the modern woman.

In this contradiction, pantyhose became a literal and symbolic embodiment of the American propensity to cover up the unseemly. As a totem of a particularly American fear—the fear of the serial killer, armed robber, suicidal housewife, S & M practitioner living amongst us, or even worse, in us—pantyhose represent a fascination nestled deep in our national psyche: the idea that the average citizen, your neighbor, could harbor a dark or maybe even deadly secret, the idea that something so genteel could be so depraved, the idea that what you see may be a kind of artificial representation—the grotesque spots obscured—of what’s underneath.

The people who embody this, the crossing from apparently normal, even likeable, to deviant, easily become part of the cultural fabric of America over time. I would be lying if I said that no part of my initial desire to read Sylvia Plath’s work stemmed from an intrigue about her life—pretty, well-educated girl from the suburbs haunted by the death of her father and finally successful in her efforts to kill herself. And the list of outlaws who’ve captivated American fascination for decades because of their depiction as having been, at one point, “just like everybody else” or even “real nice and friendly” is endless—Bonnie and Clyde, Patty Hearst, Billy the Kid, Pretty Boy Floyd.

A more recent example is Colton Harris Moore, the teenage bandit who was captured after evading police detection for two years while committing burglaries—some small and some brazen (according to the Associated Press, he allegedly stole a plane in Indiana and, without any formal training, flew the plane over 1,000 miles to the islands off Florida’s coast). His popularity grew and grew as he taunted police with photos of himself and notes left at crime scenes. T-shirts were made with his picture and the words “Fly, Colton, Fly”; Facebook pages in his honor collected millions of fans; Youtube montages highlighted his achievements. Even his mother was cheering him on. When asked by a Time Magazine reporter about the crimes attributed to Colton, she said, “I hope to hell he stole those planes. I’d be so proud. But next time, I want him to wear a parachute.”

The boy is the product of a rough life—abuse, poverty—and seems to have been in the game (this is what it was to him) for the thrill of it. In fact, locals in his hometown speculated he cared little about the money and, instead, just wanted to experience the life he never had—he sometimes broke into a house just to take a bubble bath or steal ice cream from the freezer. In the Bahamas, Moore allegedly broke into a bar just to watch TV. A month before his ultimate capture, Moore left a handwritten note and $100 at a veterinary clinic in Raymond, Washington:

Drove by, had some extra cash. Please use this cash for the care of animals.

Colton Harris-Moore, (AKA: “The Barefoot Bandit”)

Camano Island, WA.

And it was this idea that made him so endearing to so many—maybe he was just a normal kid, good-natured at heart, who had somehow crossed a line. It is the friendly, good-looking, socially engaged person who goes bad who captures our imagination.

It is an appropriate coincidence that Colton Harris Moore goes by the nickname “Colt,” a word that conjures images of the Wild West, an indomitable animal in an indomitable terrain. The Colt revolver, like nylons, is as American as pie; both were freedom bestowing and empowering. Nylons allowed a woman the freedom to live her life without the restrictions of a garter belt. Now, with nylons, she could dance the jitterbug without fear of her hose falling down. She could wear shorter skirts without showing her garter belt or any skin.

The Colt revolver was a gun that fit discreetly at the waist. Even a woman could carry a handgun inside her clutch. In fact, one trope of the quintessentially American hard-boiled detective story is the sultry and glamorous woman who walks into the private eye’s office after hours and, after a shocking confrontation in which she confesses her involvement in the crime being investigated, the cool and composed dame pulls a revolver from her purse. Of course, the woman is always dressed in a fitted and very classic suit, her hair is perfectly coifed, and her legs are long and sleek in a pair of nude pantyhose.

///