\

THE MATERIAL

Kelly Ramsey

-

In the last year, since reading that Mary Ruefle ended a lifelong practice of journal writing at the age of forty, I’ve begun to question my own journal habit. I write in one each morning, and often at night, and in free moments at work, and in a tiny secondary journal while walking. The vast majority of each entry’s content is self-indulgent, full of dailiness and anxiety, repetitive, and consumed with health obsession and its self-perpetuating cousin, the Times Well blog. But in the rare instance in which my brain produces a new idea, that sainted flash in the pan, I’ve usually—thankfully—written it down in the journal. I draft stories longhand, and if there’s not a stack of blank printer paper around, I’ll start the story in the journal. It’s where I record my research, and it’s a storage vault for scraps of language that might be useful later.

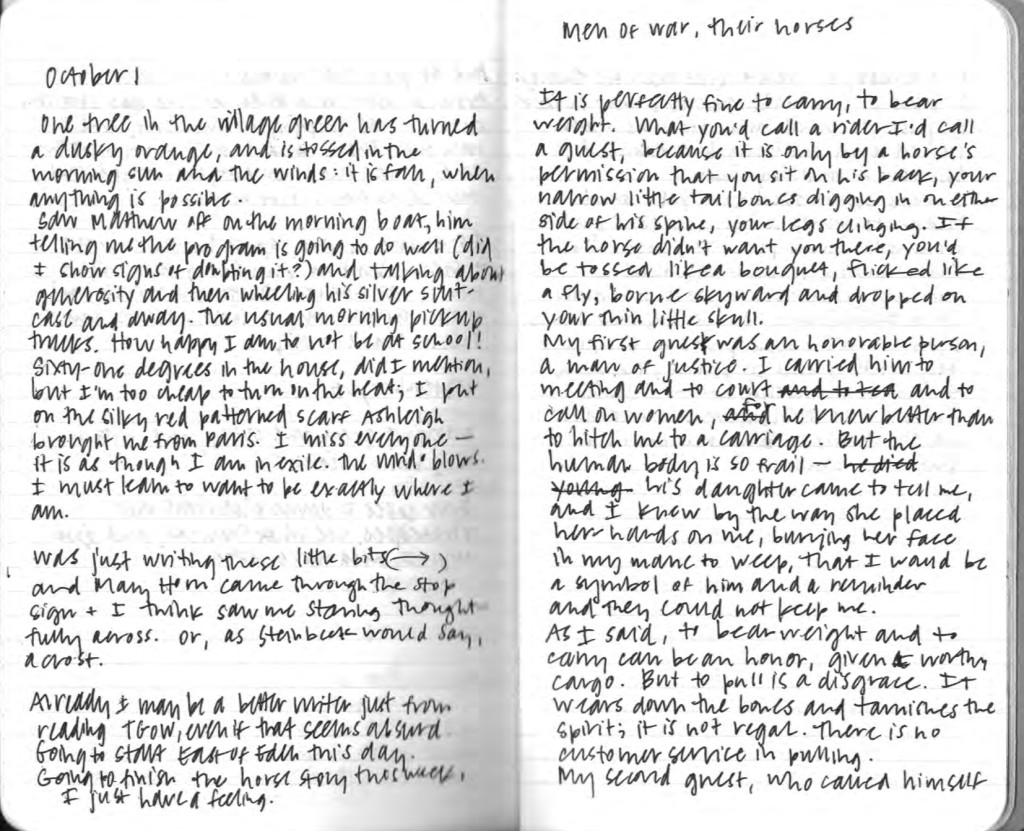

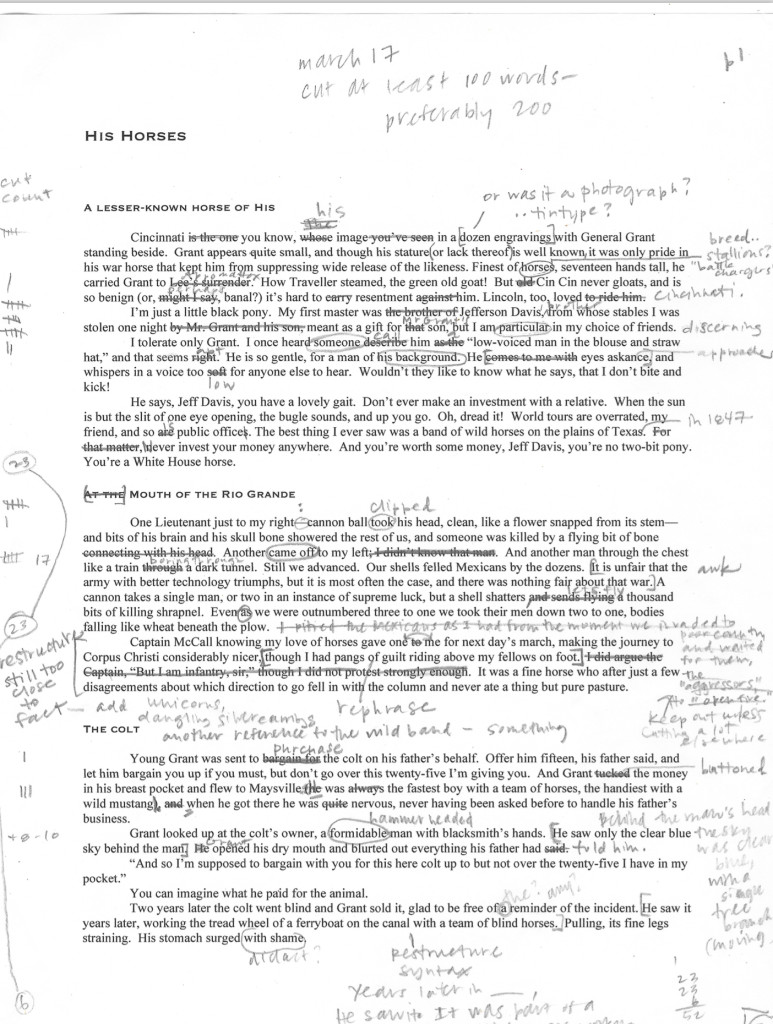

If you asked how the story about Ulysses S. Grant came to be, I might have said, “I read some parts of his memoir and noticed he talked about horses a lot.” But that’s just not what happened. This journal makes clear that originally (on October 1, 2012, to be precise) there was begun a story with the concept, “Men of War, Their Horses.”

-

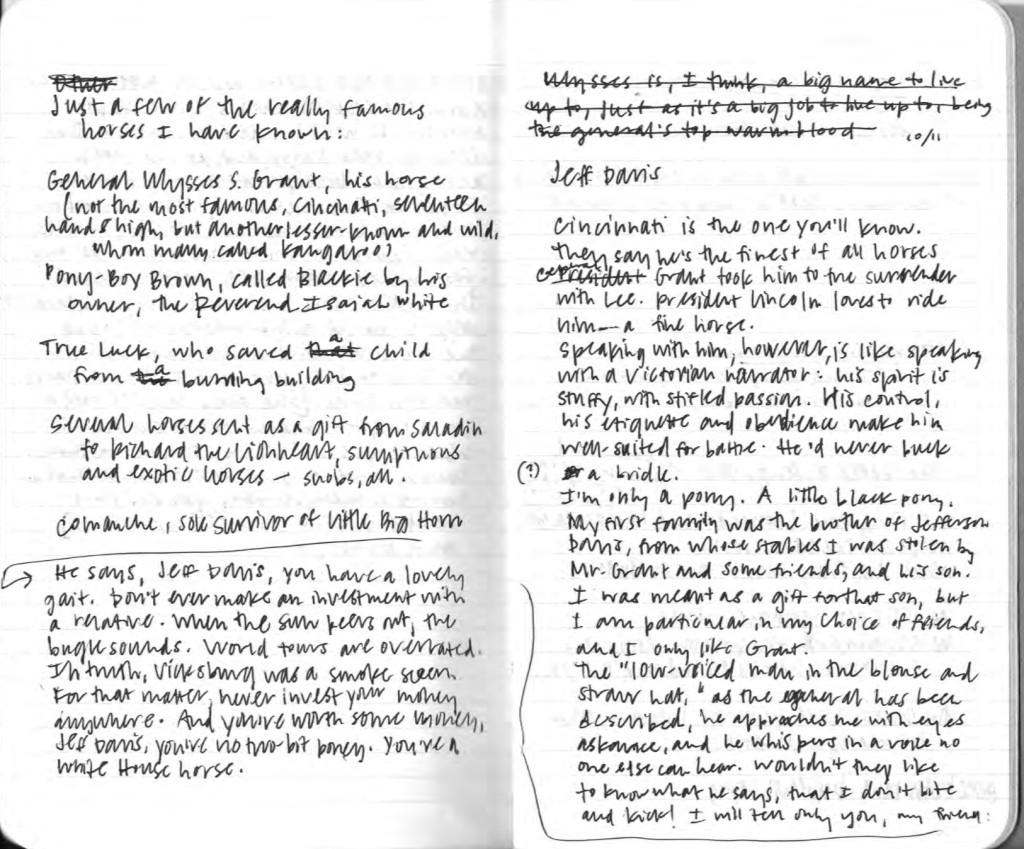

It appears, then, that “several horses sent as a gift from Saladin to Richard the Lionheart” did not interest the writer, by mid-October, nearly so much as the rivalry she imagined between Cincinnati, Ulysses S. Grant’s most well-known horse, and another equine darling of the General’s, Jeff Davis.

-

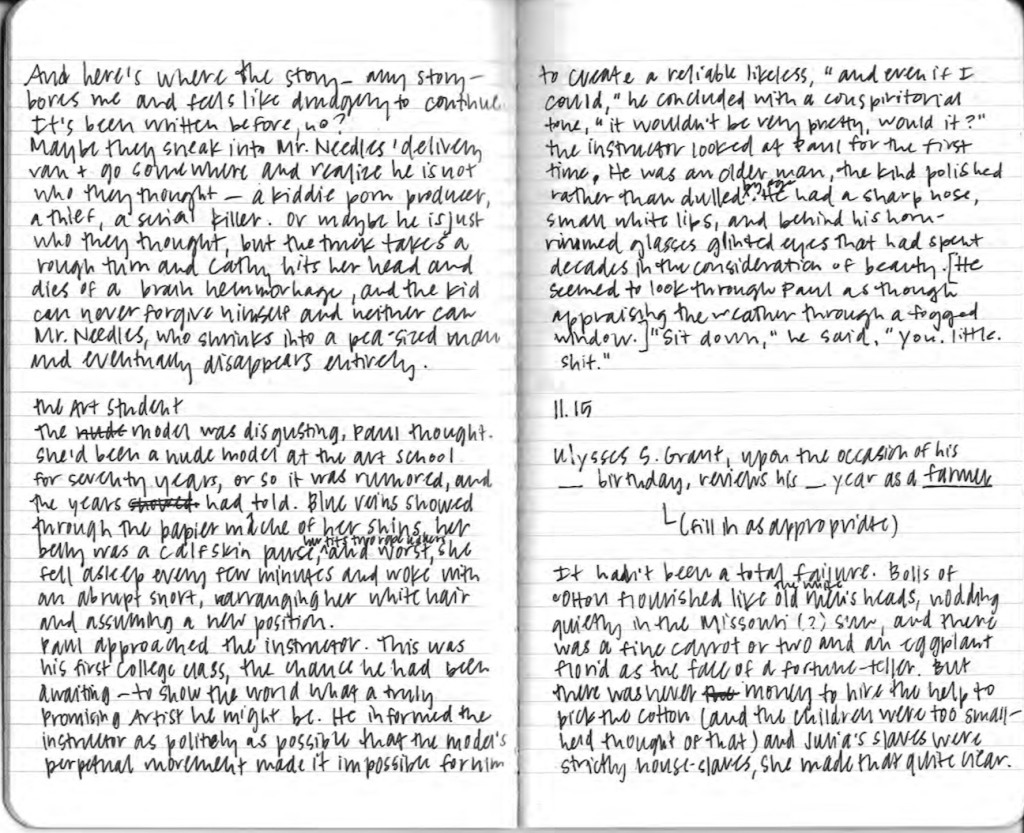

So it appears that the fascination of Grant and his horses gradually and inevitably drew the writer into Grant’s orbit.

-

And one day, maybe in March or April of 2013, she dropped the references to other horses and the story belonged to Grant, as if he’d claimed it for himself, snatching that bridle clean out of the hands of history’s other horsemen.

-

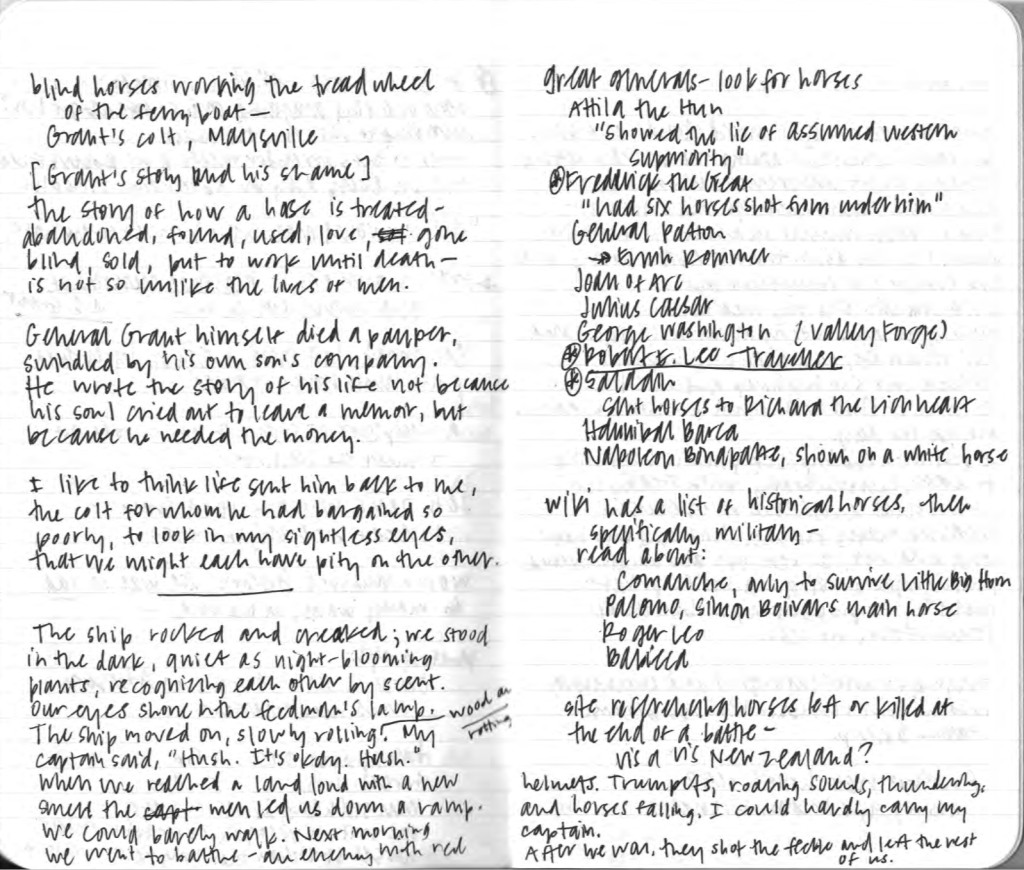

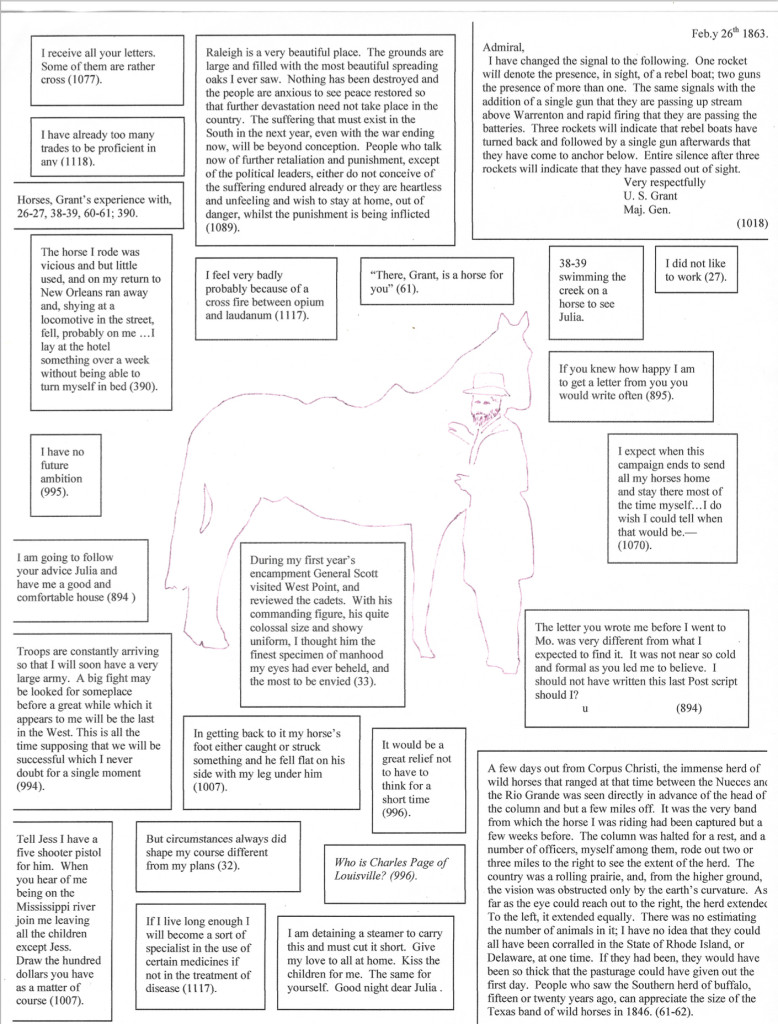

She bought his autobiography, read it scattershot, and assembled a matrix of favorite quotations. She tried to track his life through his horses.

-

And enter the months or years of meticulously picking the sentences’ teeth.

I use the third person because, in all honesty, until Callie Collins asked me to look for this material, I’d forgotten how the story came to be. It seems like some other person did this work, and I’m just digging up the relics. But that person, whose handwriting looks so familiar? Bless her (bless her heart, as they might say in Texas) for keeping a journal.