\

THE MATERIAL

Alexander Lumans

-

The origin of this story’s premise of missing one’s appointment of death has to be my Grandfather Hutchins. He (my mother’s father) was the first grandparent of mine to die (while I was still very young). But before that, when he was a Captain in the U.S. Army Air Corps during WWII, he managed to miss four different flights. All four of those flights ended up crashing. We only know the story behind two of these. He was bumped off of one flight by his Colonel. The other, he and my grandmother were returning from Cuba, and they had planned on taking an army transport plane so they could bring their dog back to the States. At the last minute, they decided to leave the dog in Cuba and took a civilian plane instead.

There’s something powerful to me about that pattern of evasion, one in whose wake so many people would find themselves either thinking: “The universe is telling me I’m supposed to die in a plane crash and I just keep getting cheated,” or “The universe is telling me I am destined for greater things.” I don’t believe in either one of those. But I wanted to tell the story of someone who desired to embrace that supposedly inevitable death rather than avoid it at all costs. It’s like having Lieutenant Dan Syndrome: you want to die in the jungle battle but Forrest keeps carrying you out.

-

Basically, all my fiction comes back to Magic: the Gathering cards. Surprise, surprise. Here is one of my favorites: “Wheel of Fortune.” I’ll spare you the gaming lesson (and why this card is awesome); I've written about the Wheel of Fortune before and written about Magic before, too.

I think I keep coming back to this card as both metaphor and literal element because of its splendidly memorable artwork and because of the possibilities that it represents in terms of storytelling. Spin the wheel for your character. Give them a new obstacle or reward. Do it again.

Magic: the Gathering inspires me to no end. You could pick three cards at random from its multitudes and immediately have the elements for a surprising story, or at least a bizarre scene. I think that was why I was never a great Magic player: I wanted to use certain cards because their names sounded so cool or they had great art (rather than using other cards because they were powerful and synergistic).

-

Photo courtesy of Greg Hume.

Photo courtesy of Greg Hume.The aardwolf is forever slighted by the aardvark: the latter will always come before the former in the dictionary. While, yes, aardvarks are not without their innate merits (e.g., the only fruit that it eats is called the “aardvark cucumber”), I thought it was about time someone recognized the wit and nobility of the majestic aardwolf.

I often have animals in my work. I’ve been trying to work against it because sometimes the animals can be easy crutches (see: every dog killing story ever) or, in some cases, they might be better replaced with an actual speaking person. But I was able to do both here: a talking aardwolf! I didn’t plan on him being able to talk. But then I wrote this into the earliest draft: "'Seems just as implausible a thing as a talking aardwolf,' answered the aardwolf." I knew I had to embrace that implausibility if the story was going to go anywhere worthwhile.

-

Photo courtesy Tambako the Jaguar.

Photo courtesy Tambako the Jaguar.An obligatory picture of an aardwolf’s long sticky tongue. Yes, it had to be chopped off.

-

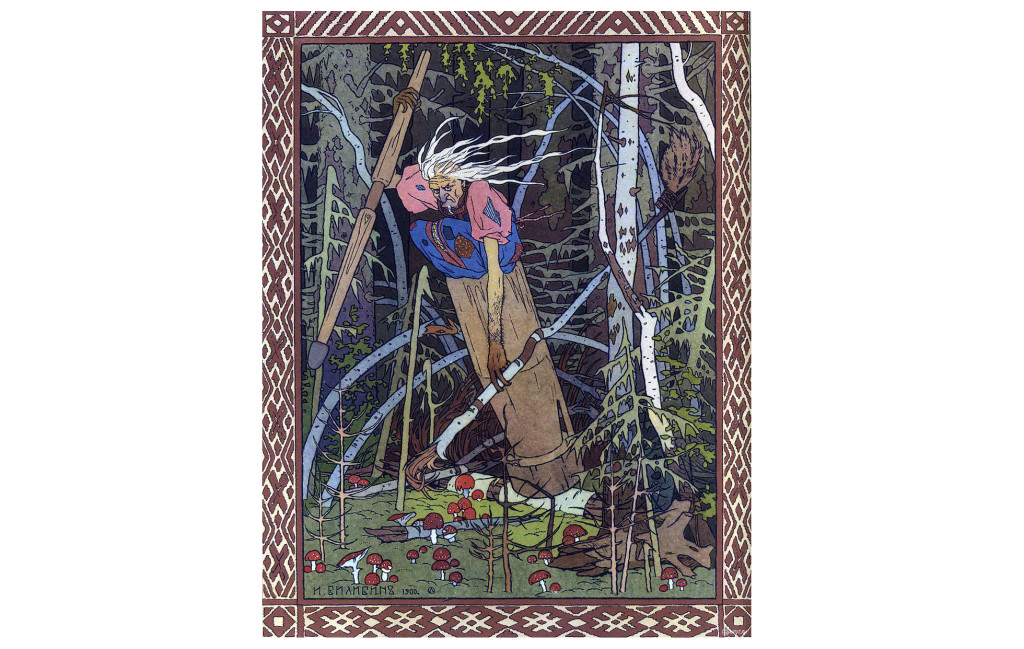

According to Russian folklore, Baba Yaga is a thin and deformed crazy witch with iron teeth who lives in a house on chicken legs that screeches all the time. Yes, you read that right. She does use a broomstick (she uses it to sweep away all traces of herself, which is how she flies), and she has three horsemen servants (Red, Black, and White). The more I learned about her, the more I knew she had to appear in some story of mine—mostly because she’s not your typical neighborhood witch, which makes her all the more attractive as a character, even a minor one.

In this case, she seemed like the perfect figure to convincingly predict the soldier’s death and grant the aardwolf the ability to speak. I am drawn a lot to not only mythology, but also misremembered or conflicting mythologies. Just researching Baba Yaga I found all kinds of different interpretations of her powers and her appearance. No single one was perfectly accurate (perfect accuracy in this case is a myth in and of itself), so I used the parts of story I thought were the weirdest. You have to embrace that ability of stories to eat, digest, and spit out other stories (which everyone from Cormac McCarthy to Neil Gaiman has talked about).

-

Here’s Baba Yaga’s ridiculous house.

-

I cannot begin to count the number of times I watched Beastmaster on TBS on Saturday afternoons as a kid. (Probably a few more times than Volunteers.) Besides being a narratively powerful film with—what else?—amazing animals (which I am sure inspired the talking aardwolf), Beastmaster has stuck with me over the years in very clearly visual ways. The image that inspired this story’s battlefield scene is a long shot of the Beastmaster riding down a desert path lined with spears, flags, and bodies strung up on crosses. It feels like the most haunting moment on his quest. And that’s what I aim for in fiction: to haunt you in whatever way I can.